From Refugee to Representative: How 1971 Shaped My Journey and My Gratitude to the UK

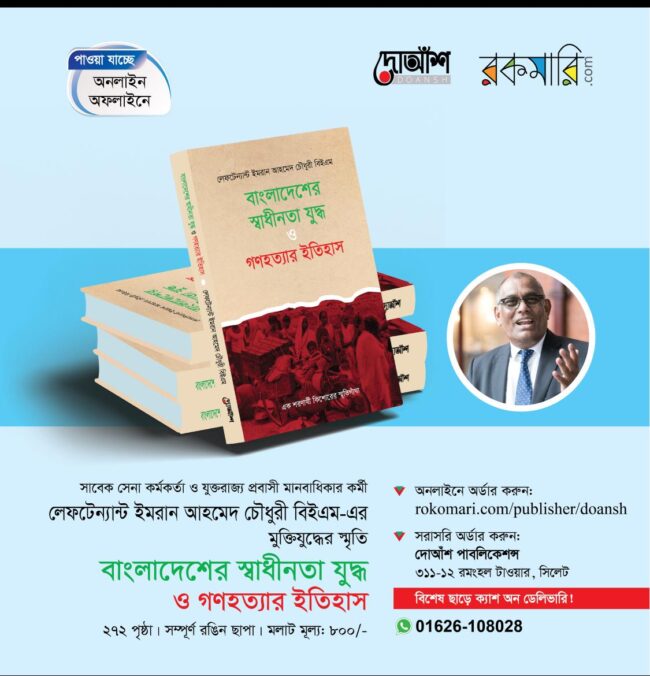

Imran Chowdhury BEM

In the summer of 1971, I was just eleven years old—too young to understand the full weight of the politics around me, but old enough to know what it meant to flee your home, to be hungry, cold, and scared. I was one of the millions forced to become a refugee during the Bangladesh Liberation War. My family fled our home in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), escaping the atrocities of a military crackdown that devastated our people and left our land in ruins.

We ended up in a refugee camp across the border in India. The conditions were harsh—monsoon rains flooded tents, sanitation was poor, food was scarce, and the cold became bone-chilling as winter approached. Yet amid that bleakness, something extraordinary happened: the world noticed. Britain noticed.

What I remember most vividly is the constant chatter of the radios at the refugee camps. They spoke of international support, of British parliamentarians visiting the camps, of food parcels arriving, of Oxfam’s tireless relief work, and of Britain’s role in backing our nation’s birth. Even as a young boy, I understood that people far away were trying to help. They didn’t have to—but they did. And it made all the difference.

A War for Freedom, and a World That Cared

1971 was not just a regional conflict. It was a humanitarian catastrophe that shook the conscience of the world. Operation Searchlight, launched by the Pakistani army on March 25th, was a violent attempt to suppress the Bengali nationalist movement. It led to mass killings, the systematic rape of women, and the forced displacement of over 10 million people into India.

The refugee camps in places like Tripura, Assam, and Meghalaya quickly overflowed. Families were sleeping under plastic sheets or huddled together under tarpaulin tents. Hunger, disease, and despair were constant threats.

But in that time of darkness, the people of Britain and organisations like Oxfam emerged as true beacons of hope.

Oxfam: A Godsend in a Time of Desperation

Oxfam’s presence in the refugee camps was more than humanitarian—it was life-saving. I speak from personal experience.

One day, driven by gnawing hunger and desperation, I scooped a fistful of milk powder from a relief packet and shoved it into my mouth. I was starving. I hadn’t eaten a real meal in days. But in my haste, I began choking. The powder clogged my throat. I couldn’t breathe. I remember gasping, my vision dimming, my legs collapsing under me. In that terrifying moment, a few Oxfam relief workers rushed to my side. They acted quickly, and they saved me.

That moment is seared into my memory. I don’t know their names, but I know this: had they not been there, I wouldn’t be here today.

From the earliest days of the war to its bitter end, Oxfam remained on the ground, delivering food, medicine, clean water, and vital care to millions. To me, and many others, they were angels in plain clothes. The image of their volunteers carrying sacks of food or treating children in makeshift clinics will always live in my heart.

Their compassion shaped me. It taught me what service means. It’s part of what drove me, years later, to pursue public service myself.

British Generosity: Coats, Blankets, and Dignity in the Cold

As winter set in during November and December of 1971, the refugee camps were hit by punishing cold and continuous rain. Many of us were living in barely covered spaces, sleeping on wet earth, often with no protection from the wind or rain. Children shivered through the night. Elderly people fell ill. Death was a daily occurrence.

Then came another miracle—from the British public.

Across the UK, people donated coats, jackets, scarves, and blankets. Boxes filled with warm clothing and essentials were shipped to India and distributed across the camps. I remember clutching a woollen blanket one bitter night. It was thick, navy blue, and smelled faintly of soap and camphor. I don’t know who sent it, but it helped me survive the cold. That blanket wasn’t just cloth—it was warmth, protection, and the kindness of a stranger from thousands of miles away.

Those donated items didn’t just keep us alive—they restored a bit of our dignity. To this day, that memory returns every time I see a winter coat drive or a charity collection in my own community. It reminds me how generosity can travel across borders and across generations.

Diaspora Power: The Early Political Activists

Back in Britain, the East Pakistani Bengali diaspora—mostly from Sylhet—played a crucial role. Though many of them worked long hours in factories, textile mills, and restaurants, they mobilised with incredible unity. Week after week, they donated part of their wages to send back home. They organised protests, handed out leaflets in the cold, and wrote letters to their MPs. They stood outside Parliament holding signs calling for British support and the recognition of Bangladesh.

It was their persistence that made Conservative MPs visit refugee camps. And it was those visits that forced the humanitarian issue into the heart of British politics.

This was not party politics. It was moral politics. And it mattered.

Sir Edward Heath and the Conservative Government’s Role

When the Conservative Party, led by Sir Edward Heath, took office in June 1970, few could have predicted the scale of the crisis that would emerge in South Asia. But when the time came, they did not look away.

The Heath government backed humanitarian aid to India for refugee relief. British planes delivered supplies. Relief grants were approved. Aid organisations were supported. And critically, when Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was released from Pakistani custody in January 1972, the UK was one of the first stops on his journey home. He was hosted by Sir Edward Heath himself, treated not just as a political figure but as the rightful leader of a nation that had paid for its freedom in blood.

That meeting between Heath and Bangabandhu wasn’t just diplomatic formality—it was recognition. It was legitimacy. And for millions of Bangladeshis like me, it was a signal that our pain, and our struggle, had not been in vain.

Land Rovers and Nation Building

After independence, Bangladesh was a country in ruins. Entire towns were flattened, bridges destroyed, infrastructure broken. But aid continued to flow in—Britain was at the forefront.

Land Rover jeeps, gifted by the UK, became a lifeline for our scattered administration. One of those jeeps was assigned to the wing of Bangladesh Rifles where my father served. I remember seeing it for the first time: sturdy, dusty, bearing the Union Jack on the door. It wasn’t just a vehicle—it was a symbol of support from a country that had no obligation to help, but chose to.

That spirit of solidarity never left me.

From Refugee to Representative

In the 1990s, I came to the UK as a proud British Bangladeshi, carrying with me the memories of my childhood and a deep sense of gratitude. I joined the Conservative Party, not just because of policies or manifestos, but because I remembered the MPs who came to our camps, the leadership of Sir Edward Heath, and the values of responsibility and service that had shaped my survival.

Today, I serve as a Councillor for Upton Ward, in West Northamptonshire Council. I’ve also been humbled by the recognition I’ve received:

British Empire Medal (BEM)

Rose of Northamptonshire Award

Freedom of the City of London

But none of those honours mean more to me than the trust of my community. They remind me of my duty—to give back, to serve, and to make sure no one is forgotten the way we were remembered in 1971.

Standing Again, With Purpose

As I stand for re-election, I do so with a heart full of memories, and a commitment rooted in the values I learned as a child: resilience, gratitude, and service.

I know what hardship looks like. I’ve seen it firsthand. And I also know the power of compassion—from aid workers, from strangers, from political leaders who choose to care. That’s what drives me in my work today.

Our community in Upton faces real challenges—housing, transport, integration, education. These aren’t policy points on paper. They are lived realities. I bring to the table not just political experience, but the life experience of someone who’s seen both the worst of hardship and the best of humanity.

A Final Reflection

To the voters of Upton and beyond:

I am not just asking for your vote. I am asking you to continue a journey with me—a journey that began in a refugee camp in 1971, passed through the corridors of British diplomacy, and today stands in service to your families, your concerns, and your future.

Every act of British compassion—from an Oxfam worker saving my life, to a donated blanket on a cold December night—has shaped who I am. My story is not unique. It is one of thousands. But I have been given a chance to serve. And I do so with pride and humility.

In the end, public service is not about politics. It is about people.

Let’s continue building something good, together.

Imran Chowdhury BEM

Councillor, Upton Ward

West Northamptonshire Council

Proud 1971 Refugee | Conservative | Community Servant